Timeline

North Britons and Jacobites 1714 – 1837

Church of Scotland split, 1843

Fleming discovers penicillin 1928

The opening of Rootes car factory, 1963

Piper Alpha and Lockerbie, 1988

Official opening of Scottish Parliament 1999

North Britons and Jacobites 1714 – 1837

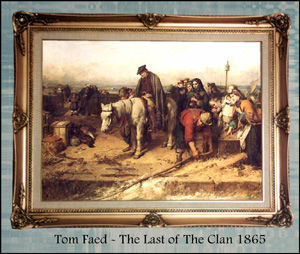

![]() During the eighteenth century, Scotland began to change into the country

we see today. In the Highlands, great wildernesses were created after the

defeat of the Jacobites when those with "get up and go" went and

Clearances replaced people with sheep. At the same time, the foundations of

the Romantic Highland Tourist Trade were laid by MacPherson's Ossian and Scotts'

Waverley.

During the eighteenth century, Scotland began to change into the country

we see today. In the Highlands, great wildernesses were created after the

defeat of the Jacobites when those with "get up and go" went and

Clearances replaced people with sheep. At the same time, the foundations of

the Romantic Highland Tourist Trade were laid by MacPherson's Ossian and Scotts'

Waverley.

A famous image of the Highland clearances

A famous image of the Highland clearances

In the Lowlands, heavy industries developed, after improvements in transport and agriculture allowed towns and cities to develop. In the countryside, the Agricultural Revolution changed its appearance by reclaiming waste land and changing it into cultivated farms.

At the same time, the rural depopulation began as more and more people began to move to the cities. This process was mapped by Webster and Sinclair in their efforts to count the number of people living in Scotland.

At the same time as these developments were taking place, Scotland became a power house of new ideas which affected Europe and are now described as The Scottish Enlightenment. The New Town of Edinburgh, now more associated with Burns and Scott than scientists and philosophers, became the showpiece of the Scottish Enlightenment.

The Victorian Era 1837 - 1901

During the reign of Queen Victoria, Scotland became one of the most industrialised countries in Europe. From Scotland's factories, mills and shipyards came products ranging from steam locomotives to textiles and ships, while coal miners toiled deep below the ground to produce the coal needed to power Scotland's expanding industries.

Millions of people took part in that process, through their labour, initiative and tenacity. Many enjoyed the benefits of industrialisation, and were able to live healthier and more comfortable lives. But many more were victims of overcrowding and disease in Scotland's expanding towns and cities. Many Scots were important figures in Scottish, and British, history during the reign of Queen Victoria. They made their marks in the military, in the administration of the Empire, adding to social progress, and rising to the top in political life as leaders of political parties, trade unions, and associations fighting for crofters' rights.

Other Scots were inventors, scientists, religious reformers, philosophers, architects, and giants of industry or of importance in the exploration and settlement of North America, Africa, Australia and New Zealand. Throughout the British Empire, Victorian Scots were to be found as settlers, missionaries, explorers, geographers and map makers.

Church of Scotland split, 1843

At its General Assembly in Edinburgh in 1843, the Church of Scotland split when nearly 200 ministers marched out to gather in another hall and form the Free Church of Scotland. The new church included more than one third of all former Church of Scotland ministers. Guided by Thomas Chalmers as their first moderator, within two years the Free Church had built 500 new churches, as well as 712 schools by 1851. Many Scots believed the disruption to have been the most significant event of the nineteenth century, and its effects were felt in Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

Modern Scotland 1901 - 1945

The first half of the twentieth century was a period of economic and political continuity. The centralisation of British industry in the English midlands after World War I reduced the Central Belt to the status of a regional industrial centre still reliant on heavy industry. The 1920's saw the decline of the Liberals as a major political force but Labour, the party which took their place, also shared many radical Liberal policies on issues such as land reform, housing, education, free trade and Scottish Home Rule. Socially this period was dominated by the hardships of WWI and the Depression which were felt more acutely in Scotland than in other regions of the UK. There was a great change in the way people spent their spare time and money with a growth in popularity of dance halls, football and the emergence of cinema.

Massive emigration, 1904

The first three decades of the century witnessed the last great movement of peoples from and to Scotland. Between 1904-13 a total of 600,000 people, almost 13% of the population, emigrated for North America and other parts of Britain. Between 1921-1931 a further 400,000 people departed. These emigrants were often the skilled and educated members of Scottish society and they took with them much of the country's self-confidence. No other European country this century has had to deal with such high levels of emigration. There was a small degree of immigration, mainly from England; by 1911 English-born Scots made up 3.5% of the population.

The 1900s also witnessed the tail-end of a large arrival of immigrants from Russia, Italy, Poland and the Baltic States, amounting to some 25,000 people. Immigration from Ireland had stalled and prior to WWI more Irish were probably leaving Scotland than arriving.

World War One starts, 1914

A

total of 147,609 Scottish people were killed during World War One, a fifth

of Britain's dead from a country that made up only 10% of its population.

On the home front, factories worked overtime and by 1917 a quarter of a million

Scots alone were making munitions. There was unrest over wages and rents throughout

the war which produced an increasingly politicised and revolutionary workforce.

A

total of 147,609 Scottish people were killed during World War One, a fifth

of Britain's dead from a country that made up only 10% of its population.

On the home front, factories worked overtime and by 1917 a quarter of a million

Scots alone were making munitions. There was unrest over wages and rents throughout

the war which produced an increasingly politicised and revolutionary workforce.

Fleming discovers penicillin 1928

While

working to find a substance fatal to bacteria but harmless to living tissue

Alexander Fleming noticed that a mould was attacking one of his cultures.

When he isolated and grew it he discovered it was of the genus Penicillium.

Although Fleming recognised the potential of his discovery it wasn't until

the Second World War that work to purify penicillin and make it effective

as an antibiotic was finally completed.

While

working to find a substance fatal to bacteria but harmless to living tissue

Alexander Fleming noticed that a mould was attacking one of his cultures.

When he isolated and grew it he discovered it was of the genus Penicillium.

Although Fleming recognised the potential of his discovery it wasn't until

the Second World War that work to purify penicillin and make it effective

as an antibiotic was finally completed.

Depression, 1929

The Depression years were extremely lean ones for Scotland. Poverty and malnutrition took their toll on adults and children alike. Scotland had one of the poorest infant mortality rates in Europe; in Glasgow in 1936 the rate was 290% higher than in Stockholm. The coal industry was in decline, while shipbuilding on the Clyde and jute production in Dundee came to a virtual standstill. Distilleries in rural areas were hit hard by American prohibition. An investigator for the Carnegie Trust recorded that the workforce became increasingly demoralised as workers experienced 'longer and more frequently recurring experiences of unemployment. With drooping shoulders and slouching feet they moved as a defeated and dispirited army'. Even for those with jobs life was still harsh with low wages, poor diet and Dickensian working conditions.

Bombing of Clydebank, 1941

With the outbreak of war the Clyde became Britain's main port and in an attempt to stop production in its shipyards and engineering works the Luftwaffe blitzed Glasgow over two nights in March 1941. Clydebank was pounded by 200 planes for a total of 15 hours. The town and its factories, including the massive munitions plant at Singers, were completely destroyed with only seven houses remaining untouched. Within six weeks, however, some of the bigger factories were back in production and by Christmas the majority of the necessary repairs had been made. It was at Clydebank that the 'Mulberry Harbours', the pierheads which made possible the Allied invasion of Normandy in 1944, were constructed.

Post World War Two 1945 -

The post-war period was one of great change for Scotland. Successive governments made genuine attempts to improve Scotland's economic ills, investing large amounts of money and resources to improve the country's infrastucture, industry and standard of living. In politics, the country witnessed the emergence of the Scottish National Party and spurred on by a stark choice between independence and the status quo the people of Scotland gradually came around to the concept of devolution.

The opening of Rootes car factory, 1963

The Rootes car factory in Linwood produced the great hope of Scottish industry, the Hillman Imp. The factory, like the steel mill at Ravenscraig and the British Motor Corporation's truck and tractor factory at Bathgate, was built in an attempt to broaden and modernise the country's industrial base.

However, these high profile operations were dogged by high transport costs and poor industrial relations. The quiet success of the period was the electronics industry which produced the type of products more suited to Scotland: high in value but low in bulk. In 1959 7,500 people were engaged in the electronics industry but this rose to 30,000 by 1969.

UCS work-in starts, 1971

In 1913 one-fifth of all shipping produced was Clyde-built. By 1971 there were only 8,500 men working in five shipyards organised into the Lower and Upper Clyde Shipbuilders.

UCS went into receivership in June after the Conservative government refused it a £6m loan. The work-in, where workers worked on as normal but without being paid, was a new tool for strikers.

Public sympathy was on the side of the token 300-or-so workers who took part and this was backed up with monetary contributions; the organisers built up an immense fighting fund which received a £5,000 contribution from John Lennon and Yoko Ono.

The ploy worked in the short-term; in February 1972 the Government caved-in and retained two of the yards and sold off another to Marathon for oil-rig building.

Silicon Glen 1980s

The big electronic companies like IBM and Motorola were attracted to Scotland by government-provided financial and material inducements. By the 1980's there was a big enough concentration of electronics firms in Scotland's Central Belt to merit a nickname: Silicon Glen.

The new jobs created here replaced those haemorrhaging from the traditional industries of coal, steel and shipbuilding. The demolition of Ravenscraig steel mill in 1996 was symbolic of the near death of Scottish heavy industry.

In 1996 the new electronics sector produced 35% of Europe's PCs and 12% of the world's semi-conductors and directly employed 55,000 people. There are some worries though that Silicon Glen's multinational companies have not developed an industry which is self-sustaining. Indigenous companies generally act as sub-contractors providing the less technologically advanced products.

Piper Alpha and Lockerbie, 1988

![]() Scotland made international headlines for all the wrong reasons in 1988. In

July the Piper Alpha oil platform, overloaded and ill-maintained, exploded

killing 167 people. The Cullen Inquiry into the disaster found Piper Alpha's

operators, Occidental, guilty of seriously inadequate safety procedures.

Scotland made international headlines for all the wrong reasons in 1988. In

July the Piper Alpha oil platform, overloaded and ill-maintained, exploded

killing 167 people. The Cullen Inquiry into the disaster found Piper Alpha's

operators, Occidental, guilty of seriously inadequate safety procedures.

The remains of Pan Am flight 10

Five months later a bomb brought down a Pan Am jumbo jet over Lockerbie, killing all 258 passengers on board and a further 11 people on the ground. Two Libyans, suspected of the bombing, were tried, under Scots Law, in the Netherlands.

Dolly the sheep, 1997

Dolly was the first mammal to be cloned from a cell of another adult animal. She is genetically identical to her twin sister, the creature from which her DNA was taken, yet her twin is more than four years older than her. She was created by scientists at the Roslyn Institute near Edinburgh and her existence has unleashed a global debate on the ethics of cloning with the prospect of human cloning looming large on the ethicists' agenda.

Official opening of Scottish Parliament 1999

Official opening of Scottish Parliament 1999

The Scottish Parliament was officially opened on 1 July 1999 by Her Majesty

The Queen. There had been an earlier failed attempt at devolution in 1979,

half-heartedly promoted by a Labour government given fright by an emergent

SNP crying: 'It's Scotland's Oil'.

The Scottish Parliament was officially opened on 1 July 1999 by Her Majesty

The Queen. There had been an earlier failed attempt at devolution in 1979,

half-heartedly promoted by a Labour government given fright by an emergent

SNP crying: 'It's Scotland's Oil'.

A new chapter:

the opening

of the Scottish parliament

Two decades of Tory domination of the Scottish Office budget and the country's political life meant that by the time of Labour's landslide victory in the General Election of May 1997, devolution was firmly back on the agenda.

In the referendum in September 1997 Scotland voted 'Yes' to devolution: 75% for a parliament and 64% that it should have tax-varying powers. With a parliament in Scotland, the consititutional map of the UK has changed once again.