Timeline

Neolithic and Bronze Ages 4000 - 750 BC

Romans in Scotland AD 80 – 399

Beginnings of Scotland 400 – 1000

Early Medieval Scotland 1000 – 1174

Neolithic and Bronze Ages 4000 - 750 BC

The

first farmers appeared in Britain around 4000 BC, marking the beginning of

the Neolithic (new stone age) period. It was at this point that the landscape

of Scotland began to be shaped into the way we see it now.

The

first farmers appeared in Britain around 4000 BC, marking the beginning of

the Neolithic (new stone age) period. It was at this point that the landscape

of Scotland began to be shaped into the way we see it now.

Before farming began, Scotland was covered with woods of varying kinds and

a wide range of animals lived here - bears, wolves, elk, wild cattle, wild

pig and smaller mammals such as squirrels and hedgehogs. The first people

began to colonise Scotland about 8,000 BC. These were hunter-gatherers and

exploited the natural resources of plants and animals that were available.

Stone pots found at Skara Brae.

| Farming originated in the eastern Mediterranean, where wild strains of modern cereal crops grew. The domestication of plants and animals such as sheep and cattle requires a different way of life from mobile hunting and it indicates a different set of beliefs and attitudes to the environment. One of the biggest impacts that farming had on the Scottish landscape was the felling of trees to clear land for agriculture. We cannot tell how farming came to Scotland and took over from hunting and gathering. It is likely that immigrants travelled from Europe to Britain and their skills and ideas were adopted by the local people. The change would have been gradual and at different rates in different places. Hunter-gatherers left very few traces of their temporary camps, but Neolithic farmers have left evidence of houses and burial buildings. In areas where trees were scarce, stone buildings such as Barnhouse and Skara Brae in Orkney survive as evidence. In wooded parts of Scotland, houses were probably built with wood and these have not survived. In the lowlands, where people have lived and farmed for millennia, traces of early settlements have been ploughed under, but aerial photography can reveal where deep pits and postholes were dug. |

There is also evidence in the form of tools, jewellery, weapons and pottery and of course the spectacular stone circles and barrows that are still standing in many places. There is no written evidence and we can only guess about many aspects of day to day life.

The arrival of the Celts in Britain is an event shrouded in mystery and myth. There is no direct physical evidence of invasion or even of immigration, but it had long been believed Celtic invasions of the British Isles were part of the north and west expansion of these Iron Age people.

As artefacts began to be found, there seemed to be a common Celtic artistic style across Europe, with characteristic curving lines and the mingling of human, animal and plant forms. There also seemed to be other shared ideas, with an emphasis on war and weapons. Even religious beliefs were thought to be shared, with all Celtic peoples having some kind of priesthood, usually known as Druids. The Iron Age people in Britain were seen as being part of the European Celtic culture and were accordingly labelled as Celts.

But many people now regard the use of the word Celtic as a term that serves

only to hide the separate identity of the Iron Age people in Britain. We have

no idea of what these people called themselves - they wrote nothing down.

But it is highly unlikely that they would have regarded themselves as part

of a European culture. Instead their loyalties would lie with family and tribe.

The idea of a common Celtic culture across Europe is now regarded by many

archaeologists as misleading. There are similarities, but there are also differences.

Instead, it is less misleading to call the people living in Britain Iron Age

people.

But many people now regard the use of the word Celtic as a term that serves

only to hide the separate identity of the Iron Age people in Britain. We have

no idea of what these people called themselves - they wrote nothing down.

But it is highly unlikely that they would have regarded themselves as part

of a European culture. Instead their loyalties would lie with family and tribe.

The idea of a common Celtic culture across Europe is now regarded by many

archaeologists as misleading. There are similarities, but there are also differences.

Instead, it is less misleading to call the people living in Britain Iron Age

people.

The Iron Age people had no writing and organic materials used in everyday life such as wood, cloth, leather and foods have not survived. We can only gain a partial idea of their culture from the few things that have survived, made from stone, pottery and metal. There is also site evidence such as the pits, banks, ditches and postholes of settlement. There are written accounts of the Iron Age people from the Romans.

Agricola advances into Scotland AD 80

The Governor of Britain, Gnaeus Julius Agricola was ordered by the Emperor Titus to advance through the Scottish lowlands. The tribes of the area below the Forth-Clyde line were incorporated into the province of Britain and a series of forts were established on this line.

Romans

in Scotland AD 80 – 399

Romans

in Scotland AD 80 – 399

The Roman control of parts of Scotland runs from AD 80 to AD 367, when heavy attacks by Picts caused the Empire to lose or give up Southern Scotland and retreat behind Hadrian's Wall. During this period the Roman army was present in Scotland in strength for only two short periods, at the end of the first century and in the middle years of the second, each period lasting about twenty years.

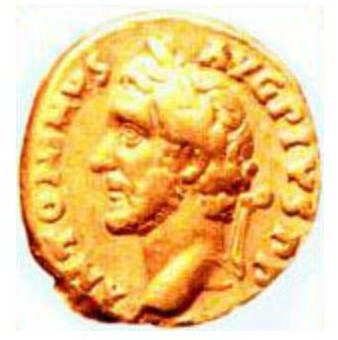

Emperor Antoninus Pius:

the Antonine Wall was built under

his rule

| Forts at key locations such as Newstead in the Borders instead exercised control over the people of southern Scotland. The Roman presence in Scotland, despite its shortness, has left behind a huge range of structures and objects that help us to piece together a picture of life for a Roman soldier in Scotland. |

After each day's march, the soldiers pitched their leather tents in rows within a camp protected by a wall of turf, often with a ditch. The marks of these camps enable us to follow the route of an army. Permanent camps left behind other remains, showing how a fort contained a blacksmith, a temple and perhaps a bathhouse.

Beginnings of Scotland 400 – 1000

The departure of the Roman legions in 410 left a power vacuum in northern Britain.

The vacuum led to centuries of struggle between "native" peoples

such as the Strathclyde Britons and the Caledonian Picts, and "newcomers"

such as the Irish Scots and the Germanic Anglians. The decisive moment in

these incessant wars was the crushing victory of the Picts an Nechtansmere

in 685. That ensured that the emerging state in northern Britain would be

a substantial kingdom rather than a mountainous rump principality.

Celtic Christianity was a unifying force throughout the age The abbey of Iona was a centre of learning and a hotbed of missionary zeal. Saints from Columba's foundation on the far west of Dalriada evangelised far-off Pictland and Northumbria. After 800, the ferocity of Viking raids forced the centres of the Celtic Church eastwards to Dunkeld and ultimately to St Andrews. But, as local princelings gave way to the King of Scots, new links were forged with royal houses in southern England and on the Continent. The Celtic influence in the Church and in society began to fade. By 1000 the tribal Gaelic speaking society of Alba was on the verge of explosive contacts with Norman Catholic Christendom.

The Abbey of Iona

Early Medieval Scotland 1000 – 1174

Over three centuries the Scots of Alba, the Angles of Lothian, the Britons of

Strathclyde, the Vikings in the West and the Normans, who originated from

France, were brought together to form the Kingdom of the Scots. They were

led by the strong and increasingly powerful monarchs of the Canmore dynasty,

founded by Malcolm Canmore and his wife Margaret.

Jedburgh Abbey

These

rulers encouraged Scotland to become more "European". Scottish feudal

nobles built their castles and looked after their tenants like nobles elsewhere

in Europe. The idea of trading in "burghs" was another European

idea which the kings encouraged by inviting men from Flanders to help create

Scotland's first towns. Scottish rulers were particularly interested in strengthening

the church in Scotland, particularly by opening new monasteries across the

country.

These

rulers encouraged Scotland to become more "European". Scottish feudal

nobles built their castles and looked after their tenants like nobles elsewhere

in Europe. The idea of trading in "burghs" was another European

idea which the kings encouraged by inviting men from Flanders to help create

Scotland's first towns. Scottish rulers were particularly interested in strengthening

the church in Scotland, particularly by opening new monasteries across the

country.

As the kingdom developed there was a particular problem with its neighbour, England. English monarchs after the Norman Conquest in 1066 were reluctant to accept Scottish independence.

The basic problem of having one island with two kingdoms was that one was bigger and richer than the other.

English

kings claimed superiority over the Scots but the Scottish kings stubbornly

refused to agree - unless they were forced to do so by powerful English armies

or, as in the case of William the Lion, by being put in jail.

English

kings claimed superiority over the Scots but the Scottish kings stubbornly

refused to agree - unless they were forced to do so by powerful English armies

or, as in the case of William the Lion, by being put in jail.

William the Lion, King of Scots, was captured by Henry II of England and forced to recognise English overlordship of Scotland with the Treaty of Falaise.

Although Henry decided not to enforce his rights over Scotland, King William was constantly trying to wriggle out of the treaty. Fifteen years later, Richard the Lionheart of England agreed that the Treaty of Falaise was obtained by force and he cancelled it.